“Take a seat in a comfortable and stable posture. Perhaps cross-legged or on a chair”, the instructor says as you settle into the meditation hall. “It’s not about a particular posture as it is about being particular about your posture” he continues. You sink into the cushion curious if you’re doing it right. Or could do it better. Instructions like these are given across the world in Zen temples, therapists offices, and now increasingly through voices in mobile apps and even schools.

They tell us to bring our attention to our breath and to expect that our attention will wander. “When you notice you’ve wandered from your breath, gently bring your attention back to the breath” the instructions say. It’s normal for our mind to wander they advice. But that with continued practice your mind will train to stay.

So where did this practice come from and how is it that it’s now become the new aspirational habit of the 21st century.

Origins of meditation

The oldest written records of a meditation practice origin in the Vedas (the early works of the Hindu religion). In this tradition it was called Dhyana meaning contemplation or reflection. The goal of Yoga, the physical activity, was a way to prepare the body for the work of Dhyana.

Meditative traditions are found in many of the world’s religions. Sometimes it’s an explicit activity like in Christian contemplation or Kabbalah but it also is a part of using the rosary. It’s said that meditation spread throughout the western and eastern world through the silk road.

In modern times, the social revolution of the 60s raised interest in Eastern traditions. With the rise of studies that show the value of meditation for mental health, meditation has become a hot commodity.

What is meditation?

The original definition of meditation is “to think or contemplate” but today it’s usage refers to focusing the mind for a period of time. Explicitly meditation is a broad set of practices that train the attentional and emotional regulation systems of the brain.

Until recently meditation has been woven deep into traditions that are typically religious. In many cases meditation was part of a monastic life or a ceremony. We’ve extracted the practice shedding a lot of the context behind it and incorporated it into apps.

Types of meditation

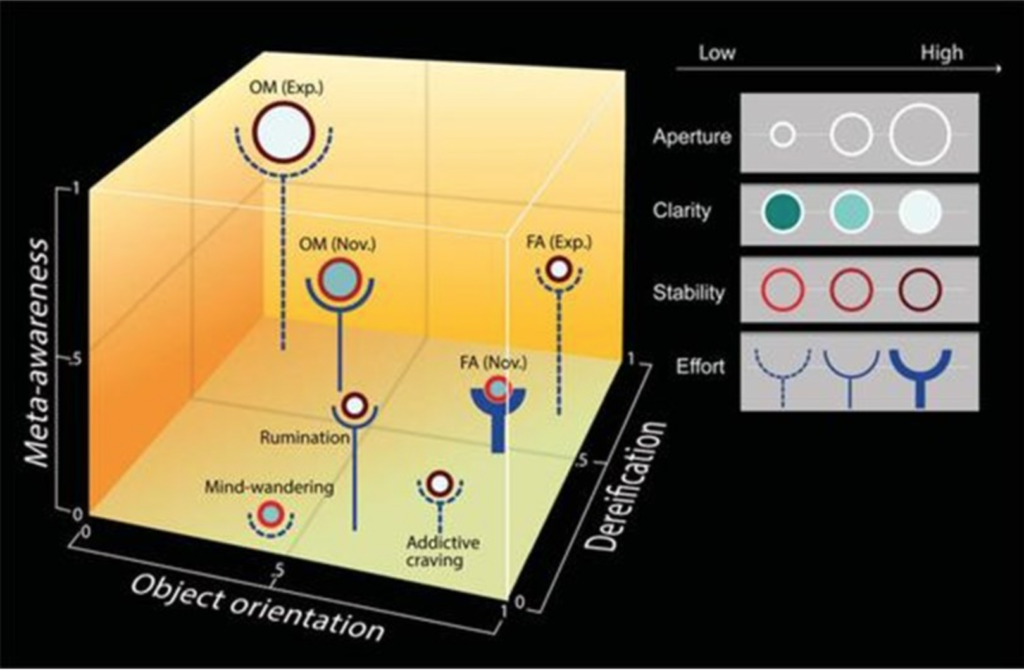

At a high level there are three types of meditation. Concentrative practices are about attending to a single object of attention (breath is a common example) to the exclusion of all others and Open Monitoring where the attention is paid to the changing experience. The third type is compassion (loving-kindness) meditation.

Concentration or focused attention

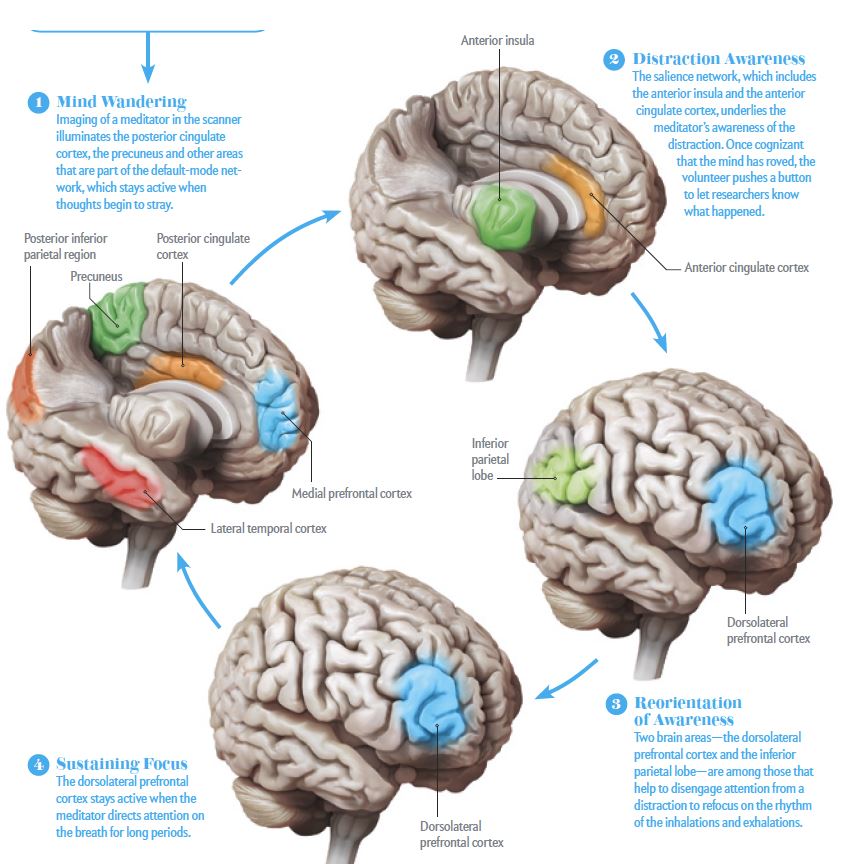

In this method of meditation the attention is focused on an object of attention – typically the breath. When you notice that attention has shifted away, the instruction is to bring your attention back to the breath. In order to keep doing this you nurture three skills of attention. First, you recognize that your attention has drifted. Second, you disengage the attention from the new object, and thirdly you bring the attention back to the breath. With practice this task becomes easier and it’s almost effortless to stay with your object of attention.

These three skills create networks in our brain (alertness, orientation, and executive control) and comprise our attentional (or executive control). They give us the ability to choose to pay attention to one thing and to ignore something else.

Object-less or Open Monitoring

In object-less meditation or open monitoring there isn’t a primary object of attention. But in order to be able to do open monitoring, your start by cultivating concentration first. In this style of meditation all distractions are included, observed, and let go. But this isn’t easy, as the natural inclination of mind is to grasp and follow an object of distraction. But in time, the skill of letting go is cultivated and the mind notices the distraction and lets go of it in a fluid motion.

In this practice, the mind develops the ability to decenter – the ability to take a step back from the thoughts while being sensitive to the body and environment. This reduces the level of automatic reactivity to thoughts and experiences resulting in lower emotional disturbance and increased satisfaction with life.

Compassion / Loving Kindness

Measuring mindfulness

Even though meditation is a single-player game, there are techniques researchers use to understand and measure the first person experience. Combined with surveys these reveal the perceived benefits of the development of mindfulness traits. There are two main impacts: state – changes that are happen while meditating or shortly thereafter. trait – changes that are stable even when not meditating.

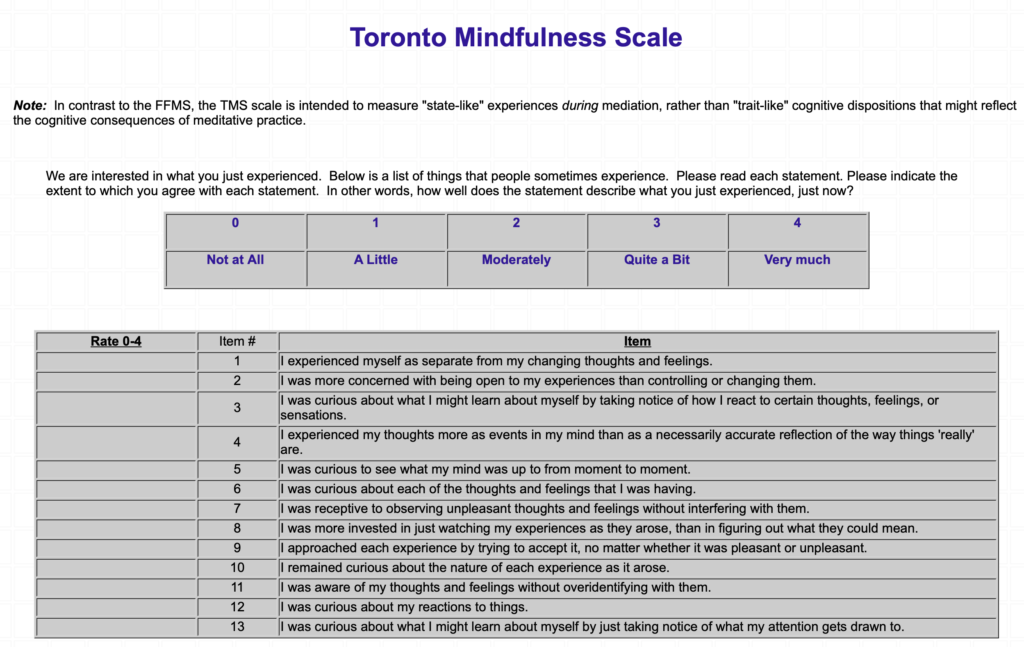

Toronto Mindfulness Scale

Developed in 2006, this mindfulness questionnaire was the first to measure state mindfulness – right after a meditation session it would ask you to rate your experience bringing insight into the meditative state. This scale measures two aspects of the meditative state: curiosity and decentering. To get the the items (3,5,6,10,12,13) and to get the decentering score add the items (1,2 ,4,7 ,8 ,9,11).

Philadelphia mindfulness scale

This scale measures mindfulness traits across two areas, acceptance and awareness. The participant is asked to answer 20 questions on a 1-5 (Never to very often – known as the Likert Scale).

1. I am aware of what thoughts are passing through my mind.

2. I try to distract myself when I feel unpleasant emotions.

3. When talking with other people, I am aware of their facial and body expressions.

4. There are aspects of myself I don’t want to think about.

5. When I shower, I am aware of how the water is running over my body.

6. I try to stay busy to keep thoughts or feelings from coming to mind. .

7. When I am startled, I notice what is going on inside my body.

8. I wish I could control my emotions more easily.

9. When I walk outside, I am aware of smells or how the air feels against my face.

10. I tell myself that I shouldn’t have certain thoughts.

11. When someone asks how I am feeling, I can identify my emotions easily.

12. There are things I try not to think about.

13. I am aware of thoughts I’m having when my mood changes.

14. I tell myself that I shouldn’t feel sad.

15. I notice changes inside my body, like my heart beating faster or my muscles getting tense.

16. If there is something I don’t want to think about, I’ll try many things to get it out of my mind.

17. Whenever my emotions change, I am conscious of them immediately.

18. I try to put my problems out of mind.

19. When talking with other people, I am aware of the emotions I am experiencing.

20. When I have a bad memory, I try to distract myself to make it go awayThe age of mindfulness

A key idea behind meditation is that we are now more aware or mindful of everyday life. This concept of mindfulness is now part of the modern everyday vocabulary. Our smart phones can track mindful minutes and there are mindful exercises for everything from eating, running, cooking, and sex. The call to arms is to step out of our habitual auto-pilot mode and smell the roses. Be here now! exclaim book and magazine covers.

The meditation market has been growing and has crested $1B and is on track to cross $2B by 2022. With over 2,000 meditation studios (the newer version of the yoga studios) and 1,000+ apps access to meditation has become easier than before. Employers now even offer meditation programs at work.

Benefits of meditation

When left unattended the mind drifts from thought to thought and stimuli to stimuli. The circuit of the brain that operates in this unfocused mode is called the default mode network. According to research, activity of the default mode network is correlated with rumination, depression, and other less desirable states.

Training the mind to pay attention changes the brain, thickens the cortex and reduces age related thinning of the brain. The marketing pitch continues to tell us that the self-regulation aspects of our brain improves.

Meditation: The new running

Dan Harris, ABC anchor and author of 10% happier (a book and meditation app) says meditation today is like jogging was in the 1940s. The notion of running for exercise and pleasure was a strange concept back then, but now it’s considered a healthy past time. Meditation the argument goes is like exercise for our minds. After all, we know to train our bodies to stay healthy and fit but what do we do for our mind?

The analogy to exercise can be a helpful one since it tells us that this is a journey and not a one-time fix. To have an impact on our lives, meditation is a life-long practice best done consistently and not sporadically.

How do we get more mindful?

The aim of all these meditation practices is to help us be more present with our experiences in the body and the mind, with as little reactivity as possible. So to begin with, if you’re able to maintain your awareness of the experience of breathing for just one half-breath at a time, and to notice when you’ve gotten lost in thinking or reacting and simply begin again, then you’re doing it correctly.

From 10% happier website

The meditation most people are familiar with is some derivative of mindfulness meditation. The aim of this method is to increase our awareness of what’s going on. In this meditation the attention is brought to rest on an object of awareness (typically the breath). As attention drifts from the breath it’s noticed and brought back to the breath. In time the attention comes back to the breath. But as you do this you gain awareness to what’s going on in your body. You might notice a tightness in your shoulder associated with a thought about work. Or a churning in your head about something someone said.

Why the breath?

The breath is a good anchor since it’s always with us. It also can reflect the inner weather – faster or slower depending on physiological conditions. It’s also potentially problematic since it’s some what within our control. There is a tendency to breathe vs just observing the breath. It’s easy to attach significance to the quality of the breath – we might think deep and slow is better than short and shallow.

Sounds

In addition to the breath there are many other objects of concentration that can be used. It’s possible to use sounds ( a specific sound or even just environmental sounds) as objects of meditation.

A practice that has some following is the notion of sound baths. The idea behind this practice is the use of various harmonic frequencies can help bring the mind to focus.

Visual

Visualizations. Candle flames. etc

Body sensations and scanning

Vipassana.

Other kinds of meditation

Concentration meditation. Metta. Chakra. etc

Who is meditating?

I fear not the man who has practiced 10,000 kicks, but I do fear the man who has practiced one kick 10,000 times. -Bruce Lee

Bruce Lee

Little by little the mindfulness muscle starts to develop. We catch ourselves as we’re about to get angry. The ever flexible mind starts to build a set of loops that take place automatically. Where we might have drifted off in thought at a traffic light a thought pops up urging us to pay attention. Like a vigilant gatekeeper it chastises, cajoles, and praises us for the work we’re doing.

It labels parts of us as helpful or unhelpful to our practice. It chases the vain thoughts around the mind.

- Goals of concentrative meditation practices

- Concentrating on your object of attention to the exclusion of everything else develops single-pointed attention. One in which you merge with the object. These are set to result in meditative ecstasy (Jhanas). These Jhanas as outlined are the path to discovering enlightenment.

- Non-duality and concentration practices: Criticisms

- These practices assume the “doer” identity. A person who meditates. So they reinforce the sense of self.

- Korean zen master quote: Bringing the attention back is like putting a rock on a patch of grass. When you stop the grass pops right back up. Is this of any value?

- Nondual meditation practices?

- Zen and Shikantaaza

- In this “just sitting” meditation there isn’t an object of attention. There is just sitting. Like a big aperture

- Dzogchen:

- Big sky meditation

- Loch Kelly glimpses

- Tibetan Mahamudra

- Self-inquiry

- Korean Zen, Ramana Maharishi: Who am I?

- Zen and Shikantaaza

- Guided nondual meditation practices